Connected Tech Keeps Officers Safe and Ups Department Trust

Law enforcement officers face the unknown every day, from stopping suspicious lurkers and serving warrants to handling crimes in progress. They walk into dangerous situations with little information and make split-second decisions that impact their own safety and that of fellow citizens. Meanwhile, criminals continue to evolve their techniques, using technology to commit crimes and evade detection.

Innovative connective technology, which provides officers new tools for their arsenal and levels the playing field, helps police departments adapt to the supercharged world of modern crime fighting. Devices that used to be the stuff of science fiction films have become reality, including body-worn video cameras and handhelds equipped with analytics and communication features.

“Technology in law enforcement is absolutely something we depend on for most of our police work,” says Precinct 1 Constable Alan Rosen of Harris County (Houston), Texas, which recently deployed body-worn cameras to officers. “The face of law enforcement is going to dramatically change in the coming years as we use this technology to solve cases and improve our work.”

SIGN UP: Get more news from the StateTech newsletter in your inbox every two weeks

Automatic Body Cameras Increase Trust

The new gear enhances situational awareness, transparency, evidence collection and officer safety and training. As agencies around the country realize these benefits, a growing number of connected officers patrol the streets.

At Rosen’s agency — serving the nation’s third most populous county — officials worked with CDW˙G and Panasonic to launch a pilot program with the Arbitrator body-worn camera and Dell EMC’s Isilon storage solution. After initial success, the agency plans to deploy almost 2,500 Arbitrator cameras across the sheriff’s office and eight constable precincts. Despite the advantages, some express reservations about the technology. For instance, critics worry that officers can simply turn cameras on and off at will.

For Harris County, such concerns have not been borne out, says Rosen. He instead foresees a positive impact on the department and the community. “We vetted the technology for a long time,” he says. “The way we use them, it is activated as soon as you turn on the patrol car’s police lights.” The dashboard camera automatically activates too.

For Harris County, such concerns have not been borne out, says Rosen. He instead foresees a positive impact on the department and the community. “We vetted the technology for a long time,” he says. “The way we use them, it is activated as soon as you turn on the patrol car’s police lights.” The dashboard camera automatically activates too.

The devices protect officers and give investigators and prosecutors a way to get right into the crime scene without risking a single life, Rosen says. It’s even simple to upload and aggregate data.

“The video is wirelessly transferred to servers as soon as officers come within 50 yards of the precinct. Right now, we have the cameras rolled out to 45 officers. The goal is for anyone working on the street on patrol or criminal warrants to have one.”

Cloud-Based Video Makes Room for More Eyes on the Street

Body cameras such as those used in Harris County — along with GPS tags, mobile fingerprint consoles, facial recognition cameras and license-plate recognition cameras — transform police work. They also create safer, more informed and efficient officers and improve trust within communities.

Body cameras such as those used in Harris County — along with GPS tags, mobile fingerprint consoles, facial recognition cameras and license-plate recognition cameras — transform police work. They also create safer, more informed and efficient officers and improve trust within communities.

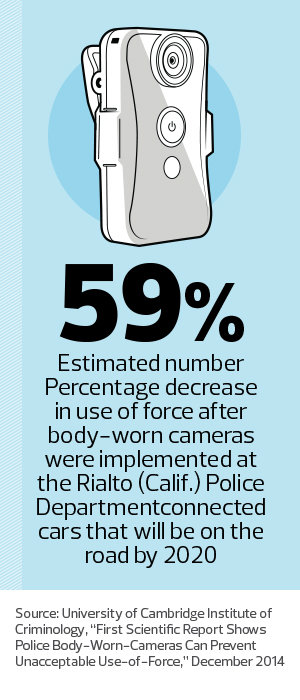

The reason is simple, according to 2014 research from the University of Cambridge Institute of Criminology, which studied the effects of body-worn cameras. The knowledge that police record interactions with citizens creates awareness of third-party surveillance ready to capture unacceptable actions. Video also deters false accusations and preserves evidence, proponents say.

In Washington state, Richland’s 60,000 residents count on the protection of the town’s 68 commissioned officers and 14 professional staffers. Five years ago, officers received daily orders the traditional way, says Capt. Mike Cobb, the Richland Police Department support operations division commander. “A sergeant stood in front of the room and read a turn-out board. Officers would transcribe information onto paper.”

Today, officers receive assignments via a 70-inch video screen complete with photos and data. Everything comes from a customized law enforcement SharePoint platform that handles shift briefings and more, Cobb says. The system displays information such as wanted bulletins, outstanding warrants, forms, briefings and contact information.

“The chiefs don’t have to spend hours poring over data anymore,” says Emily Pipkins, IT business analyst. “It’s all cloud-based, so they can gain access to video, audio, images, everything. The officers can get to the hosted solution on whatever device they have — mobile data terminals, rugged laptops and ruggedized Microsoft Surface Pros.”

Access will likely improve as the city rolls out a predictive analytics program. “We’ll see where offenders are in relation to locations of crime sprees,” Cobb says.

Tap into Data to Police the Big Picture

Instant access to data and information proves crucial when every moment counts, something that police in Elgin, Ill., know all too well. In the past, if officers needed information, they spent precious minutes going from resource to resource.

They accessed one system to see video streaming from community cameras, another to view crime analytics, and yet one more to check car locations. Today, officers have a single point of contact for everything. The Real Time Information Center system is enabled through Motorola’s Intelligence-Led Public Safety solutions, and aggregates all of the department’s digital resources in a single environment. The move has brought efficiency and reduced unnecessary calls, says Jim Bisceglie, lieutenant in charge of technical investigations. He recounts when a jet skier fell and was nearing a dam. “We instantly got eyes on the scene with the cameras, saw he wasn’t in distress and avoided sending a car and the fire department.”

Those benefits can only happen when departments incorporate the right “technological frame,” says Cynthia Lum, associate professor at George Mason University and the director of the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy. “The culture should be about reducing crime, not just using technology to make more arrests. We often tell agencies they have to strategize and think about ways technology can help them prevent crime.”

Harris County uses video footage from other departments to do just that, Rosen says. For instance, the video teaches what not to do while on the job. “Real-time video should be used to train officers to do a better job,” he says. “We recently used body-cam video of a shooting — not in our agency — to show what was done right and what should have been avoided.”

Elgin’s Bisceglie says video and data can be shared with other departments within a geographic area. His agency shares video with public works, traffic and fire department personnel.

“There’s definitely a proactive aspect to police technology,” he says. “So far the reaction from officers and the public has been overwhelmingly positive.”

Learn more here about how counties are managing and storing the influx of body camera data.