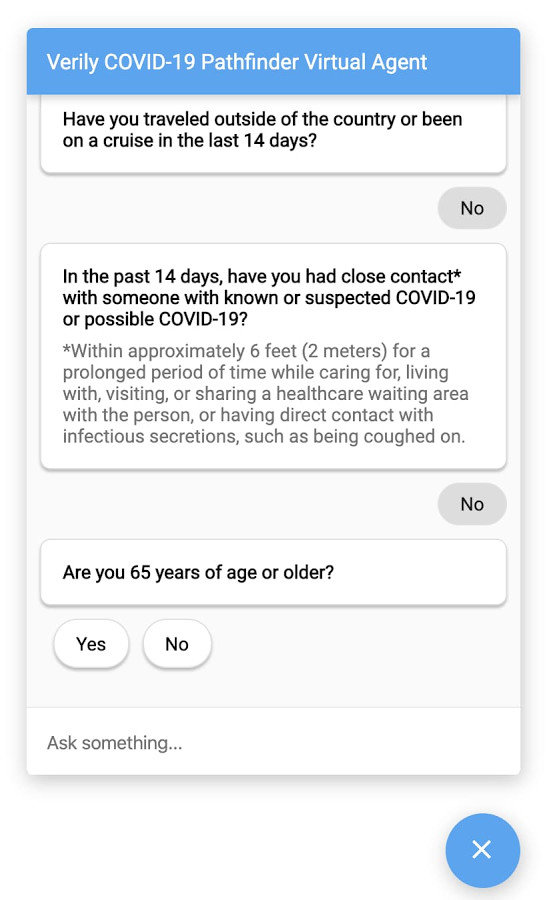

Google’sC OVID-19 virtual agent now supports 28 languages and dialects. Source: Google

With the newer version, he says, “we can deploy across multiple channels, meeting citizens where they are.”

Some people prefer to call a phone number, and others want to use a state website or mobile application. Google is supporting multiple options. “We’re also supporting a multitude of languages on the same platform,” Schroeder says. “The newest version supports 28 languages and dialects.”

In Virginia, communications technologies have been crucial to the pandemic response, driving outreach as vaccines have become more readily available.

To ensure smooth distribution of the shots, “we needed to have more people on the wait list, so that message needed to go out,” Soundararajan says. “We created a landing page to have a one-stop shop for people to register. Then we stood up a massive call center to run in parallel with that.”

Whether by call center or chatbot, that outreach is a key component of a successful public health effort. “There needs to be a constant flow of information,” he says. “If people register and they don’t hear anything, they get worried. We needed to let them know that we had them in the system, and we needed to manage their expectations.”

Data Management Technology Enables COVID-19 Response

At the same time, the data management effort was central to the overall pandemic effort. In the early days of the pandemic, systems needed to account for everything from ventilators to hospital beds.

Later, as the vaccine distribution effort ramped up, states were tasked to track myriad data points: Who needed a shot, who’d already had one, how many were available and where they needed to go.

Cheryl Rodenfels, CTO of Americas Healthcare at cloud solutions provider Nutanix, has worked with the Parkland Health and Hospital System to help the Dallas County health department in Texas leverage data to help combat the pandemic.

Pre-pandemic, Dallas County was already combining ZIP code data with healthcare information to target its breast cancer efforts. The same data infrastructure allowed the county to track things like ventilators and ICU beds. “Since they had the basics in place, when COVID came along, they did not reinvent the wheel,” Rodenfels says.

“A lot of hospitals and government organizations have great data, but they never put it together appropriately,” she adds. “For those who already had a robust program in place, this was an easy shift for them.”

While data has been the focus for many, there’s a hardware component that is also worth noting. “The hardware helps collect that data and then make that data readily available to the right people in the field,” says Michael Sparks, Zebra Technologies’ director of government sales.

For example, he says, there are a variety of sophisticated barcode scanners, printers and handheld computers that allow health workers to scan a driver’s license or an ID card, then feed that data back to the data management system. Printers then produce a barcode that can be put on a vaccine card.

“We can scan that information and confirm somebody’s appointment,” he says. “Or they can fill out their questionnaires and medical paperwork online, and then simply print a QR code so that the site administrators or the healthcare providers can simply scan that QR code instead of having to shuffle papers left and right.”

While specialized hardware may not have been top of mind in the early days of the vaccine rollout, it has proven a key element in supporting successful state efforts.

“Not every worker’s phone battery is going to last eight hours while they’re out in the field with no power to recharge it. That phone camera may not be able to decode a QR code that has been smudged a little bit,” Sparks says. “This work requires something that’s designed to be mobile, that’s designed to work in harsher elements.”