STATETECH: What are the biggest remaining points of vulnerability in states’ election infrastructure?

Norden: First of all, I think what the primaries have made clear is that the elections we’re having this fall and the elections we had this spring are very different than anyone expected at the beginning of the year because of COVID.

We are relying much more than I think anyone could have expected at the beginning of 2020 on online systems for registration, and there’s been a big dip in registration this spring, in part because the traditional ways we register have not really been possible.

I expect that there is going to be big increase, particularly in August, of use of online voter registration systems that we have in most states.

Obviously, there’s a big reliance on — where they have them — online mail ballot application systems. And while we haven’t protected those systems in the past, I think there needs to be a lot more thought and resiliency planning around how to secure those systems and what to do in the event that they fail, particularly close to things like registration deadlines or mail ballot application deadlines.

STATETECH: Does the fact that we’re moving a lot of the registration infrastructure online represent a big point of vulnerability?

Yeah. And a mail ballot applications too, right. In times past, a state may have seen 3 or 4 percent of people requesting mail ballots. We’re seeing in the primaries the numbers are much, much higher. Having an online mail ballot application system takes a lot of work. States are having a tough time keeping up with the volume, and online ballot application systems can help reduce the work that’s required to process those applications. But there’s also security issues, obviously, around using those systems — potential denial of service attacks and other potential problems.

I do think the primaries also showed — in some ways, counterintuitively — I think all the focus has been on mail voting and how we do mail voting since COVID hit. How do we ensure that mail voting works? But some of the real problems that we have seen in the primaries — in Wisconsin, Georgia, Washington, D.C. — were these tremendous lines because there were breakdowns in the polling places. A big part of it of, course, was poll workers canceling at the last minute, not having enough workers to run polling places. And a big part of it was people requesting mail ballots and not getting them.

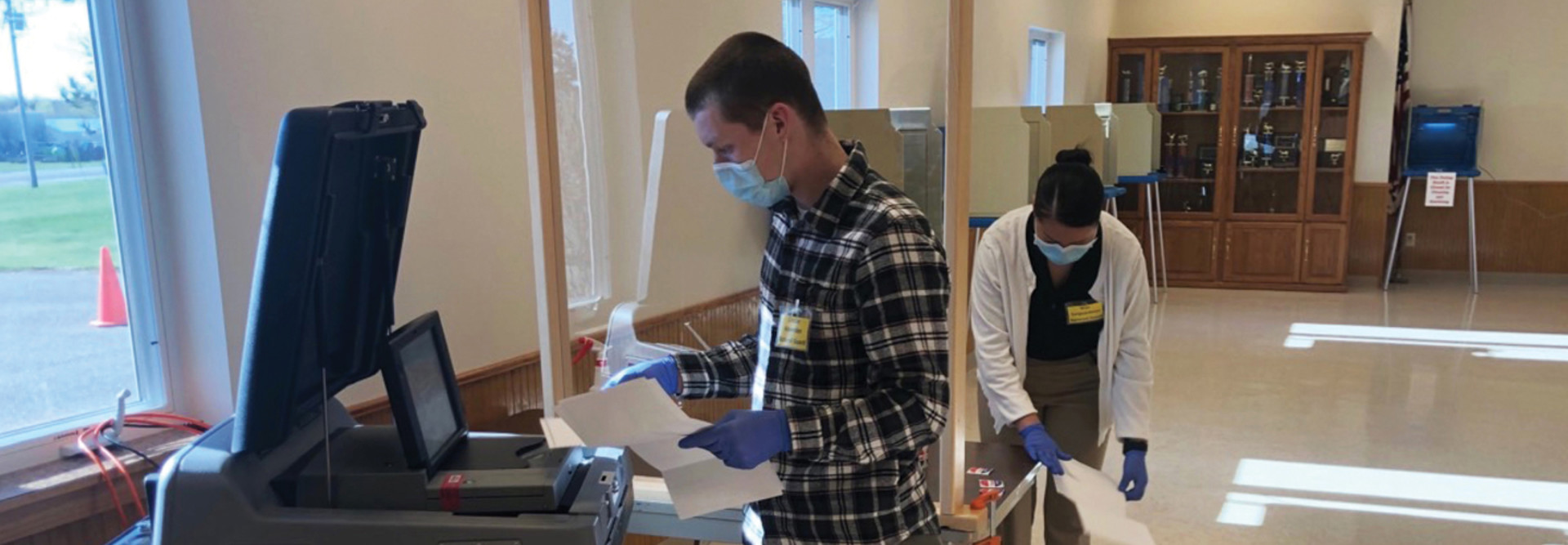

Photo: Brennan Center

Lawrence Norden, director of the Brennan Center’s election reform program, says election officials should "prioritize that potentially your systems are going to fail."

But there was a third factor, which is systems failing, particularly in a place like Georgia with new voting systems and not having appropriate backups and good training for backups. Georgia is the most obvious recent example where the poll books failed, the voting machines failed, and either the poll workers didn’t have the backup resources or weren’t trained properly to print out the paper poll book, continue processing to break out the emergency paper ballots.

We saw that in Virginia Beach this year, and to some extent in Los Angeles, when their e-poll books failed, and the result was just extremely long lines in polling places. So, I would say those are the three things that I’m most focused on around election security. Not that in any of those examples so far, there’s been a security breach that we’re aware of, but I think the accidents and security risks are kind of opposite sides of the same coin. When you have breakdowns, even if they are not through malicious actions, they give you a clue as to what could go wrong if there were cyberattacks against systems.

MORE FROM STATETECH: Explore this infographic to discover how to protect voter information.

STATETECH: STATETECH: How does the Brennan Center prioritize which measures should be undertaken to help ensure election integrity?

Norden: Our biggest focus right now, and it will be through the election, is the backup plan, the resiliency. I think secondarily, we’d like to see post-election audits. Michigan had a very successful risk-limiting audit of its presidential primary. But at this point, I think one of the other lessons of the 2020 primaries — and, unfortunately, we have no choice because of COVID — but big technological changes at the last minute can lead to problems, particularly in big elections. We can go all the way back to the Iowa caucuses and their attempt to deploy a new system. But I think in Georgia, a lot of the problems that they had in the recent primaries was just that poll workers and voters were not familiar with the new systems. Trying to do big technology changes at the last minute — if you can avoid it, you probably shouldn’t do it. Although I think it’s unavoidable to some extent, given all the changes that we’re seeing in elections.

To me, that means prioritize that potentially your systems are going to fail. Your systems are going to fail because they’re new, or there are software bugs, or because of a cyberattack, and have the backup plans in place to make sure that even if they fail, it’s not going to disrupt the elections in a way that people aren’t going to be able to vote or have their votes be counted. So that’s our No. 1 priority, making sure all those resiliency plans are in place. There’s still time to do that.

VIDEO: Hear from cybersecurity experts about the top election security threats.

STATETECH: And what are those key resiliency measures that need to be in place?

Norden: In the polling place, it’s a backed-up poll book. Most places are not using electronic poll books. And it’s emergency paper ballots in those places that are using ballot-marking devices. Those are the really big things in the polling place. And provisional ballots, of course, and having enough provisional ballots. There were reports of places running out of provisional ballots in Georgia. Those are the three things in the polling place.

And then for online systems and for mail ballots, it’s being prepared. If the online systems go down, having a redirect page to preserve voter registration attempts. To capture voters’ information if they are requesting absentee ballots and the system goes down, so that you can contact them later. Things like confirmation emails to voters, if they change their registration or they ask for an absentee ballot. It means offline backup registration data in case a voter registration database gets corrupted in some way, so that you can quickly go back and re-create an uncorrupted registration database.

Finally, a really big thing is giving people an opportunity to ensure that if their mail ballot application doesn’t come in for some reason or for some reason can’t be processed, contacting the voter and making sure that they have a chance to address whatever the problem is so that we can count every vote.

LEARN MORE: What is a deepfake and how can it impact the election?

STATETECH: The Brennan Center has said repeatedly that about $4 billion in funding would be needed this year to hold safe and fair elections during the pandemic. What happens if state and local agencies don’t get that funding or only get a fraction of that funding from Congress?

Norden: If they don’t get the funding, I think it’s going to be very challenging. There’s no question. I think, unfortunately, the voters are going to feel the burden of this. Election officials are adaptable, so they will move forward and run the election as much as they can, but I think Georgia and Wisconsin and all these other places where we have had problems are kind of previews of what will happen if they don’t get the resources that they need.

We’re going to see the possibility of mail ballot applications coming in and not getting the ballots back. Polling places will become more of a fail-safe for people whose mail ballot applications aren’t processed in-house. And we’re going to see long lines at polling places. I mean, that’s the danger. And I think it’s an avoidable danger and it’s a danger we want to do everything we can to avoid in this very highly polarized time when there’s a lot of questioning around the legitimacy of elections. We do not want a situation where six-, seven- or eight-hour lines are commonplace around the country.

STATETECH: What kind of training or tabletop exercises should state and local officials be conducting to ensure that they’re as prepared as they can be?

Norden: We are involved in doing some of these tabletop exercises and will be with Microsoft. I think [in August] we’re doing one for a bunch for election officials. Again, to me, it’s all around, ‘What are your backup plans?’

So, you’re online and there’s a ransomware attack. Especially with the big changes that have been made in voting that weren’t expected at the beginning of the year, what happens when those systems break down? How do you ensure that people can still vote? That, to me, is what the war-gaming needs to be for the next few months. It’s particularly in those areas where there have been big changes in elections.

Election officials have a lot of experience preparing for contingencies, preparing for system failures and having backup plans. But that’s more difficult when so much is new. So when you go from 5 percent to 75 percent of people trying to vote by mail, when you go from a minority of voters changing their registration information or registering a new one in your online portal to having the vast majority of people do so, planning for failures in those systems and what you do when those systems fail is going to be critical.

READ MORE: Find out how states are wroking with the federal government on election security efforts.